6.3 The Light-Independent Reactions of Photosynthesis: The Calvin Cycle

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the Calvin cycle

- Define carbon fixation

- Explain how photosynthesis works in the energy cycle of all living organisms

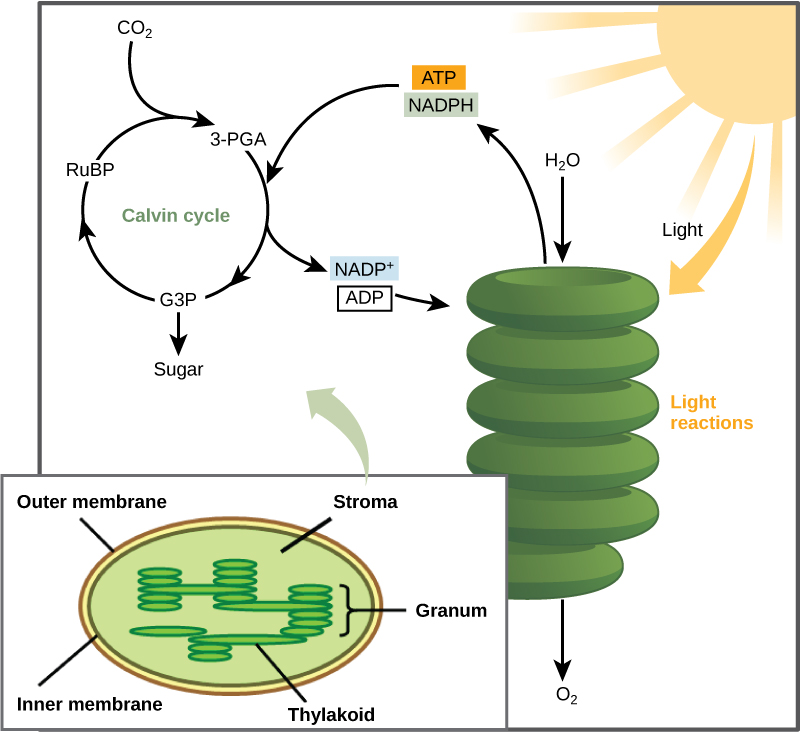

After the energy from the sun is converted and packaged into ATP and NADPH, the cell has the fuel needed to build food in the form of carbohydrate molecules for long-term energy storage. The carbohydrate molecules made will have a backbone of carbon atoms. Where does the carbon come from? The carbon atoms used to build carbohydrate molecules comes from carbon dioxide, a waste product of respiration in microbes, fungi, plants, and animals. The Calvin cycle, or the light-independent reactions, is the term used for the reactions of photosynthesis that use the energy stored by the light-dependent reactions to form glucose and other carbohydrate molecules (Figure 6.13).

The Calvin Cycle

In plants, carbon dioxide (CO2) enters the chloroplast through the stomata and diffuses into the stroma of the chloroplast—the site of the Calvin cycle reactions where sugar is synthesized. The reactions are named after the scientist who discovered them, and reference the fact that the reactions function as a cycle. Others call it the Calvin-Benson cycle to include the name of another scientist involved in its discovery. The most outdated name is “dark reaction,” because light is not directly required. However, the term dark reaction can be misleading because it implies incorrectly that the reaction requires an absence of light, which is why most scientists and instructors no longer use it.

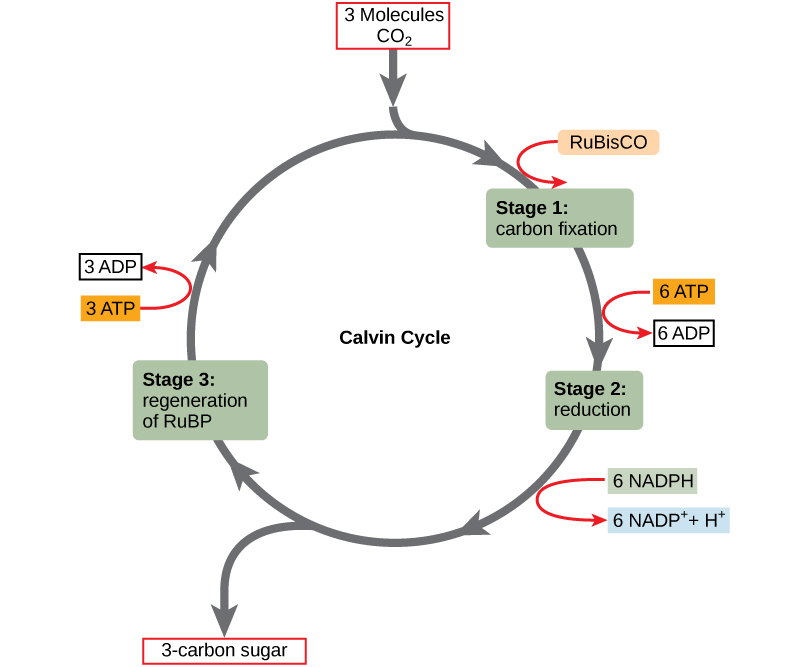

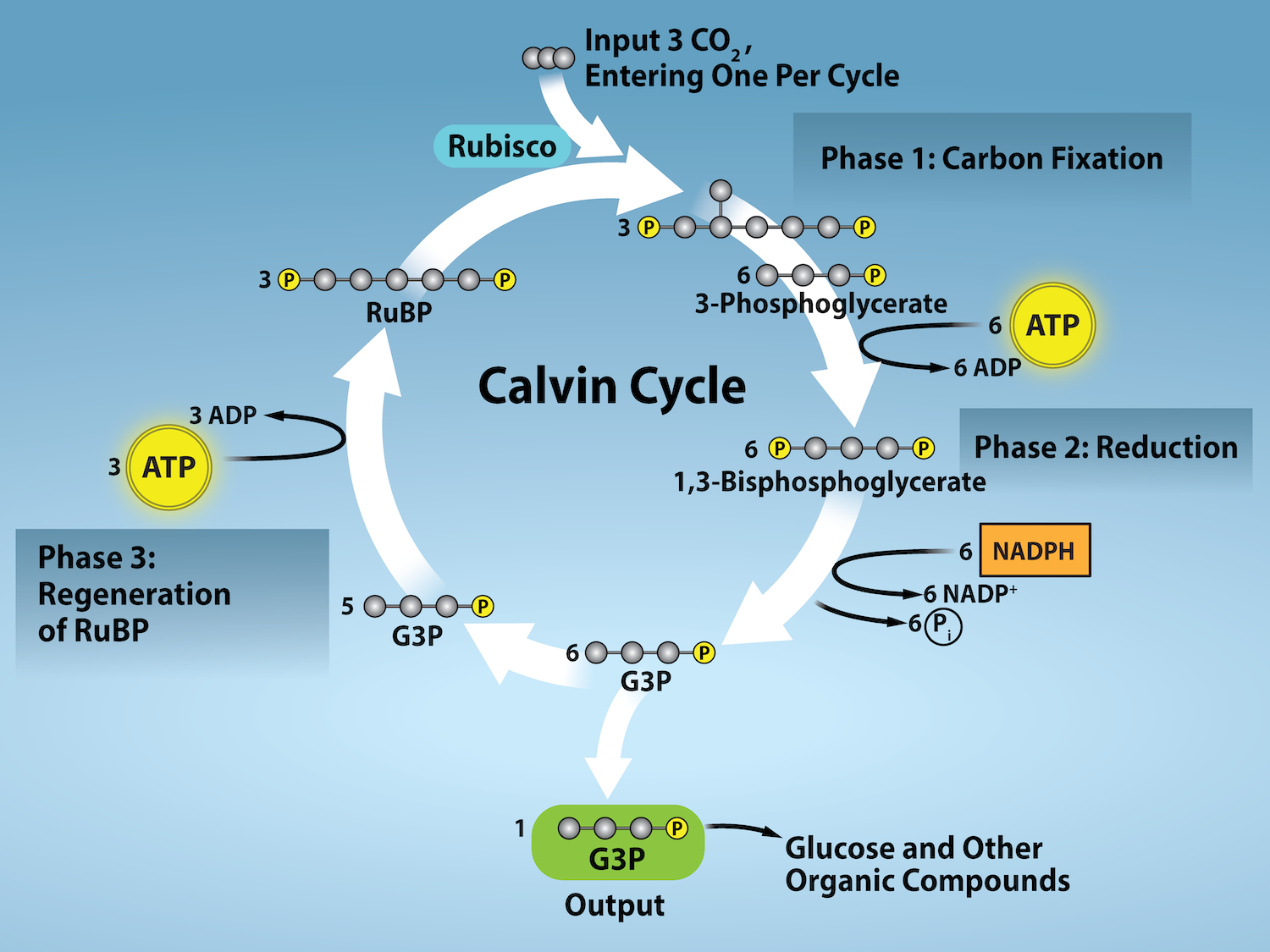

The Calvin cycle reactions (Figure 6.14) can be organized into three basic stages: fixation, reduction, and regeneration.

Stage 3: Regeneration. One of the G3P molecules leaves the Calvin cycle for the cytoplasm to contribute to the formation of other carbohydrate molecules, which is commonly glucose (C6H12O6). Because the carbohydrate molecule has six carbon atoms, it takes six turns of the Calvin cycle to make one carbohydrate molecule (one for each carbon dioxide molecule fixed). The remaining G3P molecules regenerate RuBP, which enables the system to prepare for the carbon-fixation step. ATP is also used in the regeneration of RuBP.

In summary, it takes six turns of the Calvin cycle to fix six carbon atoms from CO2. These six turns require energy input from 12 ATP molecules and 12 NADPH molecules in the reduction step and six ATP molecules in the regeneration step, Figure 6.15.

The following is a link to an animation of the Calvin cycle. Click Stage 1, Stage 2, and then Stage 3 to see G3P and ATP regenerate to form RuBP.

EVOLUTION IN ACTION

Photosynthesis

During the evolution of photosynthesis, a major shift occurred from the bacterial type of photosynthesis that involves only one photosystem and is typically anoxygenic (does not generate oxygen) into modern oxygenic (does generate oxygen) photosynthesis, employing two photosystems. This modern oxygenic photosynthesis is used by many organisms—from giant tropical leaves in the rainforest to tiny cyanobacterial cells—and the process and components of this photosynthesis remain largely the same. Photosystems absorb light and use electron transport chains to convert energy into the chemical energy of ATP and NADPH. The subsequent light-independent reactions then assemble carbohydrate molecules with this energy.

However, as with all biochemical pathways, a variety of conditions leads to varied adaptations that affect the basic pattern. Photosynthesis in dry-climate plants (Figure 6.16) has evolved with adaptations that conserve water. In the harsh dry heat, every drop of water and precious energy must be used to survive. Two adaptations have evolved in such plants. In one form, a more efficient use of CO2 allows plants to photosynthesize even when CO2 is in short supply, as when the stomata are closed on hot days. The other adaptation performs preliminary reactions of the Calvin cycle at night, because opening the stomata at this time conserves water due to cooler temperatures. In addition, this adaptation has allowed plants to carry out low levels of photosynthesis without opening stomata at all, an extreme mechanism to face extremely dry periods.

Photosynthesis in Prokaryotes

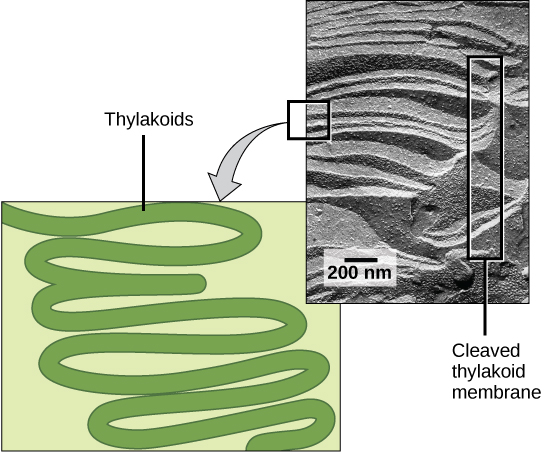

The two parts of photosynthesis—the light-dependent reactions and the Calvin cycle—have been described, as they take place in chloroplasts. However, prokaryotes, such as cyanobacteria, lack membrane-bound organelles. Prokaryotic photosynthetic autotrophic organisms have infoldings of the plasma membrane for chlorophyll attachment and photosynthesis (Figure 6.17). It is here that organisms like cyanobacteria can carry out photosynthesis.

The Energy Cycle

Living things access energy by breaking down carbohydrate molecules. However, if plants make carbohydrate molecules, why would they need to break them down? Carbohydrates are storage molecules for energy in all living things. Although energy can be stored in molecules like ATP, carbohydrates are much more stable and efficient reservoirs for chemical energy. Photosynthetic organisms also carry out the reactions of respiration to harvest the energy that they have stored in carbohydrates, for example, plants have mitochondria in addition to chloroplasts.

You may have noticed that the overall reaction for photosynthesis:

is the reverse of the overall reaction for cellular respiration:

Photosynthesis produces oxygen as a by-product, and respiration produces carbon dioxide as a by-product.

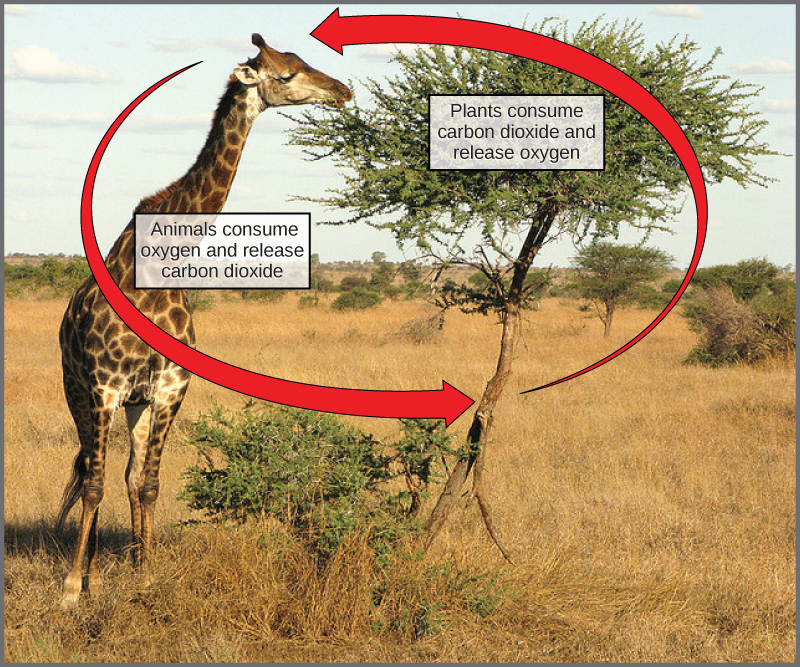

In nature, there is no such thing as waste. Every single atom of matter is conserved, recycling indefinitely. Substances change form or move from one type of molecule to another, but never disappear (Figure 6.18). CO2 is no more a form of waste produced by respiration than oxygen is a waste product of photosynthesis. Both are by-products of reactions that move on to other reactions. Photosynthesis absorbs energy to build carbohydrates in chloroplasts, and aerobic cellular respiration releases energy by using oxygen to break down carbohydrates. Both organelles use electron transport chains to generate the energy necessary to drive other reactions. Photosynthesis and cellular respiration function in a biological cycle, allowing organisms to access life-sustaining energy that originates millions of miles away in a star.

Section Summary

Using the energy carriers formed in the first stage of photosynthesis, the Calvin cycle reactions fix CO2 from the environment to build carbohydrate molecules. An enzyme, RuBisCO, catalyzes the fixation reaction, by combining CO2 with RuBP. The resulting six-carbon compound is broken down into two three-carbon compounds, and the energy in ATP and NADPH is used to convert these molecules into G3P. One of the three-carbon molecules of G3P leaves the cycle to become a part of a carbohydrate molecule. The remaining G3P molecules stay in the cycle to be formed back into RuBP, which is ready to react with more CO2. Photosynthesis forms a balanced energy cycle with the process of cellular respiration. Plants are capable of both photosynthesis and cellular respiration, since they contain both chloroplasts and mitochondria.

Exercises

Glossary

Calvin cycle: the reactions of photosynthesis that use the energy stored by the light-dependent reactions to form glucose and other carbohydrate molecules

carbon fixation: the process of converting inorganic CO2 gas into organic compounds

Media Attributions

- Figure 6.15 by Rao, A., Ryan, K., Tag, A., Fletcher, S. and Hawkins, A. Department of Biology, Texas A&M University

- Figure 6.16 by Piotr Wojtkowski

- Figure 6.17 scale-bar data from Matt Russell

- Figure 6.18 modification of work by Stuart Bassil