7.1 The Plasma Membrane Components and Structure

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand the fluid mosaic model of membranes

- Describe the functions of phospholipids, proteins, and carbohydrates in membranes

- State the role of the plasma membrane

- Discuss membrane fluidity

A cell’s plasma membrane, also called the cell membrane, defines the boundary of the cell and determines the nature of its contact with the environment. Cells exclude some substances, take in others, and excrete still others, all in controlled quantities. Plasma membranes enclose the borders of cells, but rather than being a static bag, they are dynamic and constantly in flux. The plasma membrane must be sufficiently flexible to allow certain cells, such as red blood cells and white blood cells, to change shape as they pass through narrow capillaries. These are the more obvious functions of a plasma membrane. In addition, the surface of the plasma membrane carries markers that allow cells to recognize one another, which is vital as tissues and organs form during early development, and which later plays a role in the “self” versus “non-self” distinction of the immune response.

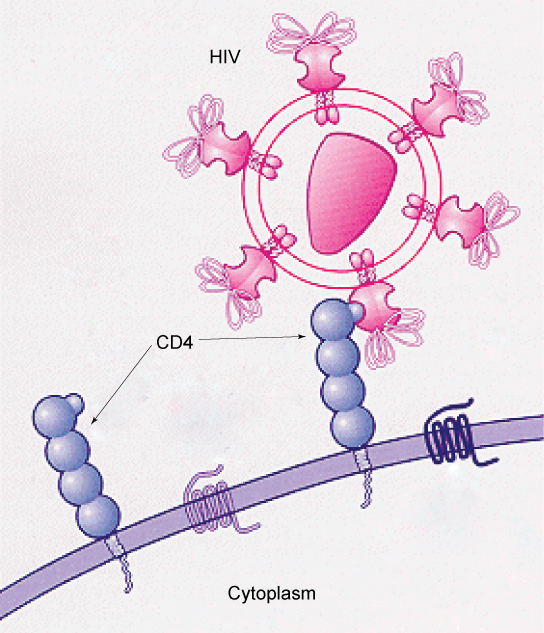

The plasma membrane also carries receptors, which are attachment sites for specific substances that interact with the cell. Each receptor is structured to bind with a specific substance. For example, surface receptors of the membrane create changes in the interior, such as changes in enzymes of metabolic pathways. These metabolic pathways might be vital for providing the cell with energy, making specific substances for the cell, or breaking down cellular waste or toxins for disposal. Receptors on the plasma membrane’s exterior surface interact with hormones or neurotransmitters, and allow their messages to be transmitted into the cell. Some recognition sites are used by viruses as attachment points. Although they are highly specific, pathogens like viruses may evolve to exploit receptors to gain entry to a cell by mimicking the specific substance that the receptor is meant to bind. This specificity helps to explain why human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or any of the five types of hepatitis viruses invade only specific cells.

Fluid Mosaic Model of the Plasma Membrane

Scientists identified the plasma membrane in the 1890s, and its chemical components in 1915. The principal components they identified were lipids and proteins. In 1935, Hugh Davson and James Danielli proposed the plasma membrane’s structure. This was the first model that others in the scientific community widely accepted. It was based on the plasma membrane’s “railroad track” appearance in early electron micrographs. Davson and Danielli theorized that the plasma membrane’s structure resembles a sandwich. They made the analogy of proteins to bread, and lipids to the filling. In the 1950s, advances in microscopy, notably transmission electron microscopy, allowed researchers to see that the plasma membrane’s core consisted of a double, rather than a single, layer.

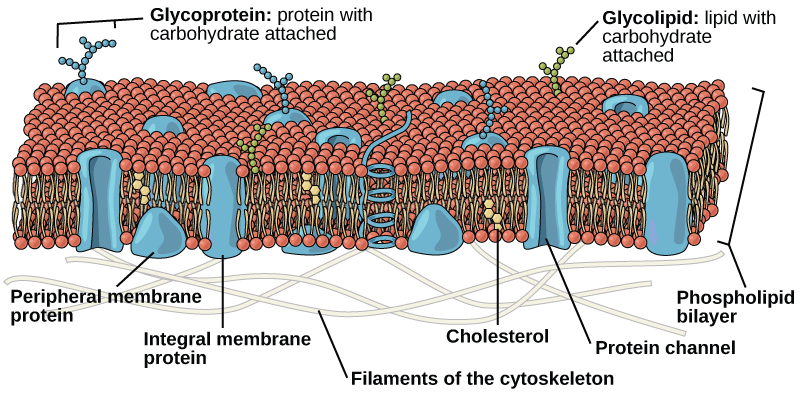

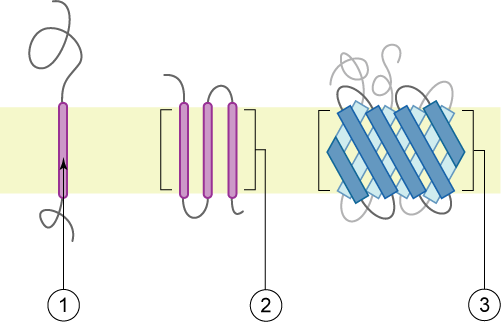

In 1972, S. J. Singer and Garth L. Nicolson proposed a new model of the plasma membrane that, compared to earlier understanding, better explained both microscopic observations and the function of the plasma membrane. This was called the fluid mosaic model (Figure 7.1). The model has evolved somewhat over time, but still best accounts for the structure and functions of the plasma membrane as we now understand them. The fluid mosaic model describes the structure of the plasma membrane as a mosaic of components—including phospholipids, cholesterol, proteins, and carbohydrates—in which the components are able to flow and change position, while maintaining the basic integrity of the membrane. Both phospholipid molecules and embedded proteins are able to diffuse rapidly and laterally in the membrane. The fluidity of the plasma membrane is necessary for the activities of certain enzymes and transport molecules within the membrane. Plasma membranes range from 5–10 nm thick. As a comparison, human red blood cells, visible via light microscopy, are approximately 8 µm thick, or approximately 1,000 times thicker than a plasma membrane.

Peripheral proteins are on the membranes’ exterior and interior surfaces, attached either to integral proteins or to phospholipids. Peripheral proteins, along with integral proteins, may serve as enzymes, as structural attachments for the cytoskeleton’s fibres, or as part of the cell’s recognition sites. Scientists sometimes refer to these as “cell-specific” proteins. The body recognizes its own proteins and attacks foreign proteins associated with invasive pathogens.

Carbohydrates are the third major component of plasma membranes. These carbohydrate chains may consist of 2–60 monosaccharide units and may be either straight or branched. They are always found on the exterior surface of cells and are bound either to proteins (forming glycoproteins) or to lipids (forming glycolipids).We collectively refer to these carbohydrates on the cell’s exterior surface—the carbohydrate components of both glycoproteins and glycolipids—as the glycocalyx (meaning “sugar coating”). The glycocalyx is highly hydrophilic and attracts large amounts of water to the cell’s surface. These carbohydrate complexes help the cell bind required substances in the extracellular fluid. This adds considerably to plasma membrane’s selective nature. Along with peripheral proteins, carbohydrates form specialized sites on the cell surface that allow cells to recognize each other. This recognition function is very important to cells, as it allows the immune system to differentiate between body cells (“self”) and foreign cells or tissues (“non-self”). Similar glycoprotein and glycolipid types are on the surfaces of viruses and may change frequently, preventing immune cells from recognizing and attacking them.

Animals have an additional membrane constituent that assists in maintaining fluidity. Cholesterol, which lies alongside the phospholipids in the membrane, tends to dampen temperature effects on the membrane. Thus, this lipid functions as a buffer, preventing lower temperatures from inhibiting fluidity and preventing increased temperatures from increasing fluidity too much. Thus, cholesterol extends, in both directions, the temperature range in which the membrane is appropriately fluid and consequently functional. The amount of cholesterol in animal plasma membranes regulates the fluidity of the membrane and changes based on the temperature of the cell’s environment. In other words, cholesterol acts as antifreeze in the cell membrane and is more abundant in animals that live in cold climates. Cholesterol also serves other functions, such as organizing clusters of transmembrane proteins into lipid rafts.

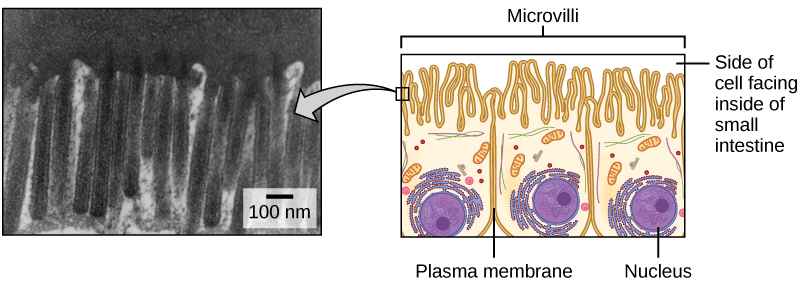

The plasma membranes of cells that specialize in absorption are folded into fingerlike projections called microvilli (singular: microvillus, Figure 7.3). This folding increases the surface area of the plasma membrane. Such cells are typically found lining the small intestine, the organ that absorbs nutrients from digested food. This is an excellent example of form matching the function of a structure.

People with celiac disease have an immune response to gluten, which is a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye. The immune response damages microvilli, and thus, afflicted individuals cannot absorb nutrients. This leads to malnutrition, cramping, and diarrhea. Patients suffering from celiac disease must follow a gluten-free diet.

EVOLUTION IN ACTION

How Viruses Infect Specific Organs

Specific glycoprotein molecules exposed on the surface of the cell membranes of host cells are exploited by many viruses to infect specific organs. For example, HIV is able to penetrate the plasma membranes of specific kinds of white blood cells called T-helper cells and monocytes, as well as some cells of the central nervous system. The hepatitis virus attacks only liver cells.

These viruses are able to invade these cells, because the cells have binding sites on their surfaces that the viruses have exploited with equally specific glycoproteins in their coats (Figure 7.4). The cell is tricked by the mimicry of the virus coat molecules, and the virus is able to enter the cell. Other recognition sites on the virus’s surface interact with the human immune system, prompting the body to produce antibodies. Antibodies are made in response to the antigens (or proteins associated with invasive pathogens). These same sites serve as places for antibodies to attach, and either destroy or inhibit the activity of the virus. Unfortunately, these sites on HIV are encoded by genes that change quickly, making the production of an effective vaccine against the virus very difficult. The virus population within an infected individual quickly evolves through mutation into different populations, or variants, distinguished by differences in these recognition sites. This rapid change of viral surface markers decreases the effectiveness of the person’s immune system in attacking the virus, because the antibodies will not recognize the new variations of the surface patterns.

CAREER CONNECTION

Immunologist

The variations in peripheral proteins and carbohydrates that affect a cell’s recognition sites are of prime interest in immunology. In developing vaccines, researchers have been able to conquer many infectious diseases, such as smallpox, polio, diphtheria, and tetanus.

Immunologists are the physicians and scientists who research and develop vaccines, as well as treat and study allergies or other immune problems. Some immunologists study and treat autoimmune problems (diseases in which a person’s immune system attacks his or her own cells or tissues, such as lupus) and immunodeficiencies, whether acquired (such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or AIDS) or hereditary (such as severe combined immunodeficiency, or SCID). Immunologists also help treat organ transplantation patients, who must have their immune systems suppressed so that their bodies will not reject a transplanted organ. Some immunologists work to understand natural immunity and the effects of a person’s environment on it. Others work on questions about how the immune system affects diseases such as cancer. In the past, researchers did not understand the importance of having a healthy immune system in preventing cancer.

Immunologists who focus on certain types of diseases or pathogens can play an important role in saving lives during specific outbreaks and pandemics. Kizzmekia S. Corbett, for example, was a research fellow and scientific lead working specifically on coronaviruses. When the COVID-19 pandemic occurred, Corbett’s deep experience and knowledge was instrumental in developing one of the main vaccines (Moderna). She is now applying that experience to other respiratory diseases and vaccine development processes.

To work as an immunologist, one must have a PhD or MD. In addition, immunologists undertake at least two to three years of training in an accredited program and must pass the American Board of Allergy and Immunology exam. Immunologists must possess knowledge of the human body’s function as they relate to issues beyond immunization, and knowledge of pharmacology and medical technology, such as medications, therapies, test materials, and surgical procedures.

Section Summary

The modern understanding of the plasma membrane is referred to as the fluid mosaic model. The plasma membrane is composed of a bilayer of phospholipids, with their hydrophobic, fatty acid tails in contact with each other. The landscape of the membrane is studded with proteins, some of which span the membrane. Some of these proteins serve to transport materials into or out of the cell. Carbohydrates are attached to some of the proteins and lipids on the outward-facing surface of the membrane. These form complexes that function to identify the cell to other cells. The fluid nature of the membrane owes itself to the configuration of the fatty acid tails, the presence of cholesterol embedded in the membrane (in animal cells), and the mosaic nature of the proteins and protein-carbohydrate complexes, which are not firmly fixed in place. Plasma membranes enclose the borders of cells, but rather than being a static bag, they are dynamic and constantly in flux.

Exercises

Glossary

Media Attribution

- Figure 7.1 by Rao, A., Ryan, K., Fletcher, S., Hawkins, A. and Tag, A. Department of Biology, Texas A&M University

- Figure 7.2 by Foobar/Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 7.3 micrograph, modification of work by Louisa Howard

- Figure 7.4 modification of work by NIH, NIAID