8.3 DNA Structure and Sequencing

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the structure of DNA

- Explain the Sanger method of DNA sequencing

- Discuss the similarities and differences between eukaryotic and prokaryotic DNA

- Describe the structure of prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes

- Distinguish between chromosomes, genes, and traits

- Describe the mechanisms of chromosome compaction

Recall the structure of nucleotides and DNA from 8.1 Nucleotides and Nucleic Acids.

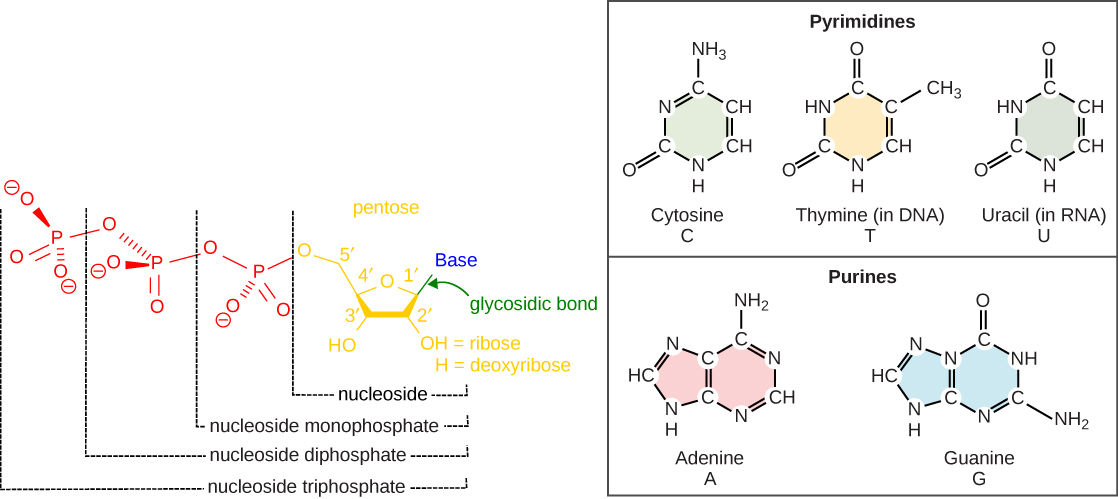

The building blocks of DNA are nucleotides. The important components of the nucleotide are a nitrogenous (nitrogen-bearing) base, a five-carbon sugar (pentose), and a phosphate group (Figure 8.9). The nucleotide is named depending on the nitrogenous base. The nitrogenous base can be a purine such as adenine (A) and guanine (G), or a pyrimidine such as cytosine (C) and thymine (T). The sugar is deoxyribose in DNA. The carbon atoms of the five-carbon sugar are numbered 1′, 2′, 3′, 4′, and 5′ (1′ is read as “one prime”). The phosphate, which makes DNA acidic, is connected to the 5′ carbon of the sugar by the formation of an ester linkage between phosphoric acid and the 5′-OH group (an ester is an acid + an alcohol). The 3′ carbon of the sugar deoxyribose is attached to a hydroxyl (-OH) group. RNA has a different sugar and set of bases than DNA. The sugar is ribose in RNA, the 2′ carbon of the sugar ribose also contains a hydroxyl group. The base is attached to the 1′ carbon of the sugar. RNA has uracil (U) and not T. In a polynucleotide, one end of the chain has a free 5′ phosphate, and the other end has a free 3′-OH. These are called the 5′ and 3′ ends of the chain.

The images above illustrate the five bases of DNA and RNA. Examine the images and explain why these are called “nitrogenous bases.” How are the purines different from the pyrimidines? How is one purine or pyrimidine different from another, e.g., adenine from guanine? How is a nucleoside different from a nucleotide?

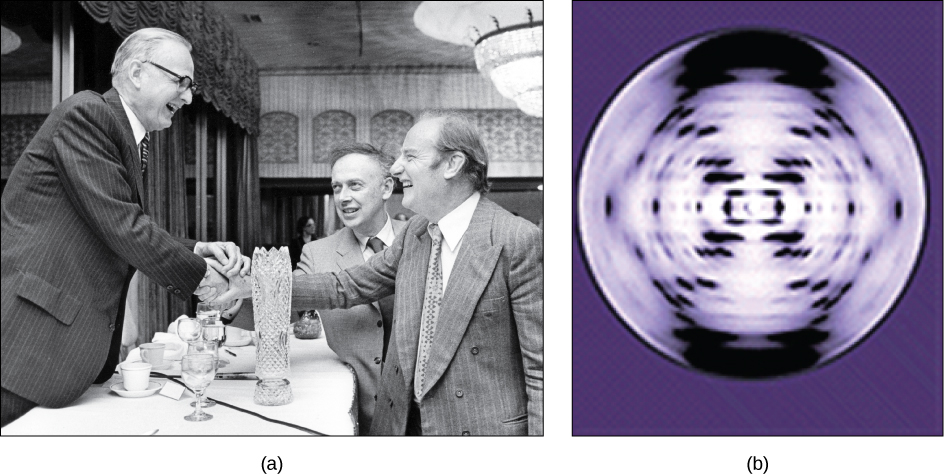

In the 1950s, Francis Crick and James Watson worked together to determine the structure of DNA at the University of Cambridge, England. Other scientists like Linus Pauling and Maurice Wilkins were also actively exploring this field. Pauling previously had discovered the secondary structure of proteins using X-ray crystallography. In Wilkins’ lab, researcher Rosalind Franklin was using X-ray diffraction methods to understand the structure of DNA. Watson and Crick were able to piece together the puzzle of the DNA molecule on the basis of Franklin’s data because Crick had also studied X-ray diffraction (Figure 8.10). In 1962, James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine. Unfortunately, by then Franklin had died, and Nobel prizes are not awarded posthumously.

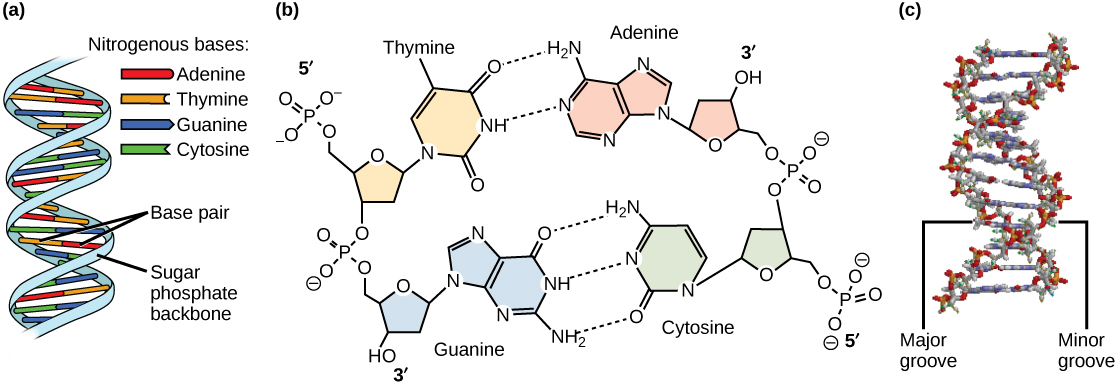

Watson and Crick proposed that DNA is made up of two strands that are twisted around each other to form a right-handed helix. Base pairing takes place between a purine and pyrimidine on opposite strands, so that A pairs with T, and G pairs with C (suggested by Chargaff’s Rules). Thus, adenine and thymine are complementary base pairs, and cytosine and guanine are also complementary base pairs. The base pairs are stabilized by hydrogen bonds: adenine and thymine form two hydrogen bonds and cytosine and guanine form three hydrogen bonds. The two strands are anti-parallel in nature; that is, the 3′ end of one strand faces the 5′ end of the other strand. The sugar and phosphate of the nucleotides form the backbone of the structure, whereas the nitrogenous bases are stacked inside, like the rungs of a ladder. Each base pair is separated from the next base pair by a distance of 0.34 nm, and each turn of the helix measures 3.4 nm. Therefore, 10 base pairs are present per turn of the helix. The diameter of the DNA double-helix is 2 nm, and it is uniform throughout. Only the pairing between a purine and pyrimidine and the antiparallel orientation of the two DNA strands can explain the uniform diameter. The twisting of the two strands around each other results in the formation of uniformly spaced major and minor grooves (Figure 8.11).

DNA Sequencing Techniques

Until the 1990s, the sequencing of DNA (reading the sequence of DNA) was a relatively expensive and long process. Using radiolabeled nucleotides also compounded the problem through safety concerns. With currently available technology and automated machines, the process is cheaper, safer, and can be completed in a matter of hours. Fred Sanger developed the sequencing method used for the human genome sequencing project, which is widely used today.

Visit this site to watch a video explaining the DNA sequence-reading technique that resulted from Sanger’s work.

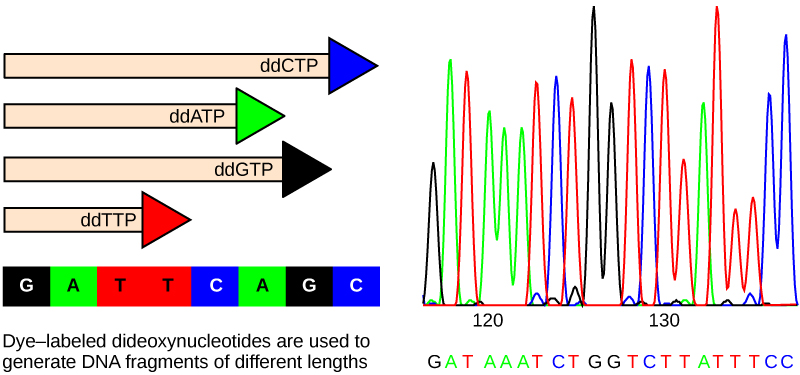

The sequencing method is known as the dideoxy chain termination method (Figure 8.12). The method is based on the use of chain terminators, the dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs). The ddNTPSs differ from the deoxynucleotides by the lack of a free 3′ OH group on the five-carbon sugar. If a ddNTP is added to a growing DNA strand, the chain cannot be extended any further because the free 3′ OH group needed to add another nucleotide is not available. By using a predetermined ratio of deoxyribonucleotides to dideoxynucleotides, it is possible to generate DNA fragments of different sizes.

The DNA sample to be sequenced is denatured (separated into two strands by heating it to high temperatures). The DNA is divided into four tubes in which a primer, DNA polymerase, and all four nucleoside triphosphates (A, T, G, and C) are added. In addition, limited quantities of one of the four dideoxynucleoside triphosphates (ddCTP, ddATP, ddGTP, and ddTTP) are added to each tube respectively. The tubes are labeled as A, T, G, and C according to the ddNTP added. For detection purposes, each of the four dideoxynucleotides carries a different fluorescent label. Chain elongation continues until a fluorescent dideoxy nucleotide is incorporated, after which no further elongation takes place. After the reaction is over, electrophoresis is performed. Even a difference in length of a single base can be detected. The sequence is read from a laser scanner that detects the fluorescent marker of each fragment. For his work on DNA sequencing, Sanger received a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1980.

Sanger’s genome sequencing has led to a race to sequence human genomes at rapid speed and low cost, often referred to as the $1000-in-one-day sequence. Learn more by selecting the Sequencing at Speed animation here.

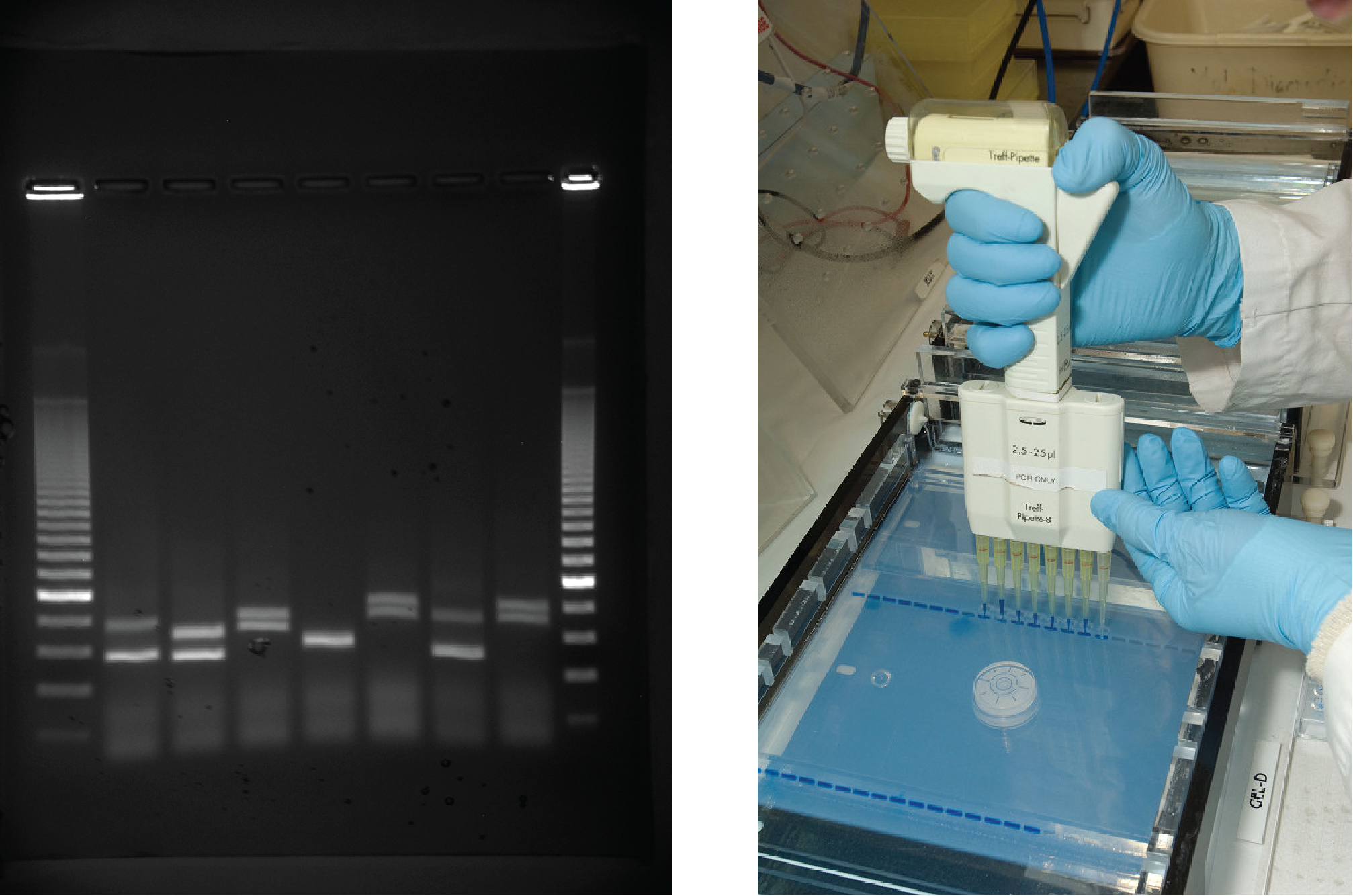

Gel electrophoresis is a technique used to separate DNA fragments of different sizes. Usually the gel is made of a chemical called agarose (a polysaccharide polymer extracted from seaweed that is high in galactose residues). Agarose powder is added to a buffer and heated. After cooling, the gel solution is poured into a casting tray. Once the gel has solidified, the DNA is loaded on the gel and electric current is applied. The DNA has a net negative charge and moves from the negative electrode toward the positive electrode. The electric current is applied for sufficient time to let the DNA separate according to size; the smallest fragments will be farthest from the well (where the DNA was loaded), and the heavier molecular weight fragments will be closest to the well. Once the DNA is separated, the gel is stained with a DNA-specific dye for viewing it (Figure 8.13).

EVOLUTION CONNECTION

Neanderthal Genome: How Are We Related?

The first draft sequence of the Neanderthal genome was recently published by Richard E. Green et al. in 2010.1 Neanderthals are the closest ancestors of present-day humans. They were known to have lived in Europe and Western Asia (and now, perhaps, in Northern Africa) before they disappeared from fossil records approximately 30,000 years ago. Green’s team studied almost 40,000-year-old fossil remains that were selected from sites across the world. Extremely sophisticated means of sample preparation and DNA sequencing were employed because of the fragile nature of the bones and heavy microbial contamination. In their study, the scientists were able to sequence some four billion base pairs. The Neanderthal sequence was compared with that of present-day humans from across the world. After comparing the sequences, the researchers found that the Neanderthal genome had 2 to 3 percent greater similarity to people living outside Africa than to people in Africa. While current theories have suggested that all present-day humans can be traced to a small ancestral population in Africa, the data from the Neanderthal genome suggest some interbreeding between Neanderthals and early modern humans.

Green and his colleagues also discovered DNA segments among people in Europe and Asia that are more similar to Neanderthal sequences than to other contemporary human sequences. Another interesting observation was that Neanderthals are as closely related to people from Papua New Guinea as to those from China or France. This is surprising because Neanderthal fossil remains have been located only in Europe and West Asia. Most likely, genetic exchange took place between Neanderthals and modern humans as modern humans emerged out of Africa, before the divergence of Europeans, East Asians, and Papua New Guineans.

Several genes seem to have undergone changes from Neanderthals during the evolution of present-day humans. These genes are involved in cranial structure, metabolism, skin morphology, and cognitive development. One of the genes that is of particular interest is RUNX2, which is different in modern day humans and Neanderthals. This gene is responsible for the prominent frontal bone, bell-shaped rib cage, and dental differences seen in Neanderthals. It is speculated that an evolutionary change in RUNX2 was important in the origin of modern-day humans, and this affected the cranium and the upper body.

Watch Svante Pääbo’s talk explaining the Neanderthal genome research at the 2011 annual TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design) conference.

Genomic DNA

Before discussing the steps a cell must undertake to replicate and divide its DNA, a deeper understanding of the structure and function of a cell’s genetic information is necessary. The size of the genome in one of the most well-studied prokaryotes, E.coli, is 4.6 million base pairs (approximately 1.1 mm, if cut and stretched out). So how does this fit inside a small bacterial cell? The DNA is twisted by what is known as supercoiling. Supercoiling suggests that DNA is either “under-wound” (less than one turn of the helix per 10 base pairs) or “over-wound” (more than 1 turn per 10 base pairs) from its normal relaxed state. Some proteins are known to be involved in the supercoiling; other proteins and enzymes such as DNA gyrase help in maintaining the supercoiled structure.

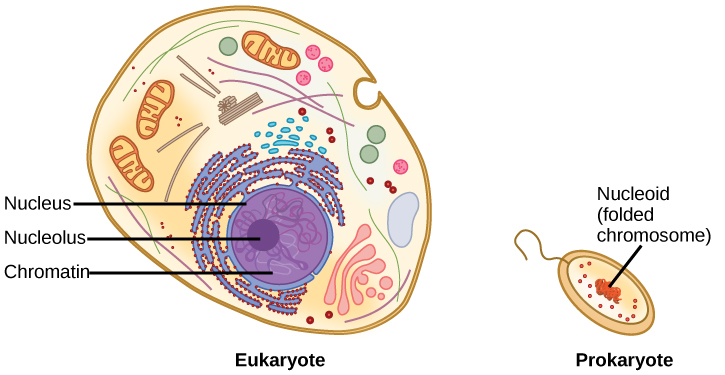

A cell’s DNA, packaged as a double-stranded DNA molecule, is called its genome. Prokaryotes are much simpler than eukaryotes in many of their features (Figure 8.14). Most prokaryotes contain a single double-stranded DNA organized as circular chromosome that is found in an area of the cytoplasm called the nucleoid region. Some prokaryotes also have smaller loops of DNA called plasmids that are not essential for normal growth. Bacteria can exchange these plasmids with other bacteria, sometimes receiving beneficial new genes that the recipient can add to their chromosomal DNA. Antibiotic resistance is one trait that often spreads through a bacterial colony through plasmid exchange from resistant donors to recipient cells.

In eukaryotic cells, DNA and RNA synthesis occur in a separate compartment from protein synthesis. In prokaryotic cells, both processes occur together.

What advantages might there be to separating the processes? What advantages might there be to having them occur together?

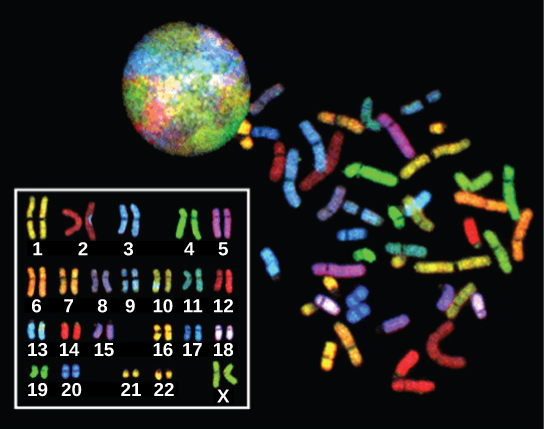

In eukaryotes, the genome consists of several double-stranded linear DNA molecules. Each species of eukaryotes has a characteristic number of chromosomes in the nuclei of its cells. Human body (somatic) cells have 46 chromosomes, while human gametes (sperm or eggs) have 23 chromosomes each. A typical body cell contains two matched or homologous sets of chromosomes (one set from each biological parent)—a configuration known as diploid. (Note: The letter n is used to represent a single set of chromosomes; therefore, a diploid organism is designated 2n.) Human cells that contain one set of chromosomes are called gametes, or sex cells; these are eggs and sperm, and are designated 1n, or haploid.

Upon fertilization, each gamete contributes one set of chromosomes, creating a diploid cell containing matched pairs of chromosomes called homologous (“same knowledge”) chromosomes. Homologous chromosomes are the same length and have specific nucleotide segments called genes in exactly the same location, or locus. Genes, the functional units of chromosomes, determine specific characteristics by coding for specific proteins. Traits are the variations of those characteristics. For example, hair colour is a characteristic with traits that are blonde, brown, or black, and many colours in between.

Each copy of a homologous pair of chromosomes originates from a different parent; therefore, the different genes (alleles) themselves are not identical, although they code for the same traits such as “hair colour.” The variation of individuals within a species is due to the specific combination of the genes inherited from both parents. Even a slightly altered sequence of nucleotides within a gene can result in an alternative trait. For example, there are three possible gene sequences on the human chromosome that code for blood type: sequence A, sequence B, and sequence O. Because all diploid human cells have two copies of the chromosome that determines blood type, the blood type (the trait) is determined by the two alleles of the marker gene that are inherited. It is possible to have two copies of the same gene sequence on both homologous chromosomes, with one on each (for example, AA, BB, or OO), or two different sequences, such as AB, AO, or BO.

Apparently minor variations of traits, such as blood type, eye colour, and handedness, contribute to the natural variation found within a species, but even though they seem minor, these traits may be connected with the expression of other traits as of yet unknown. However, if the entire DNA sequence from any pair of human homologous chromosomes is compared, the difference is much less than one percent. The sex chromosomes, X and Y, are the single exception to the rule of homologous chromosome uniformity: Other than a small amount of homology that is necessary to accurately produce gametes, the genes found on the X and Y chromosomes are different.

DNA Packaging in Eukaryotic Cells

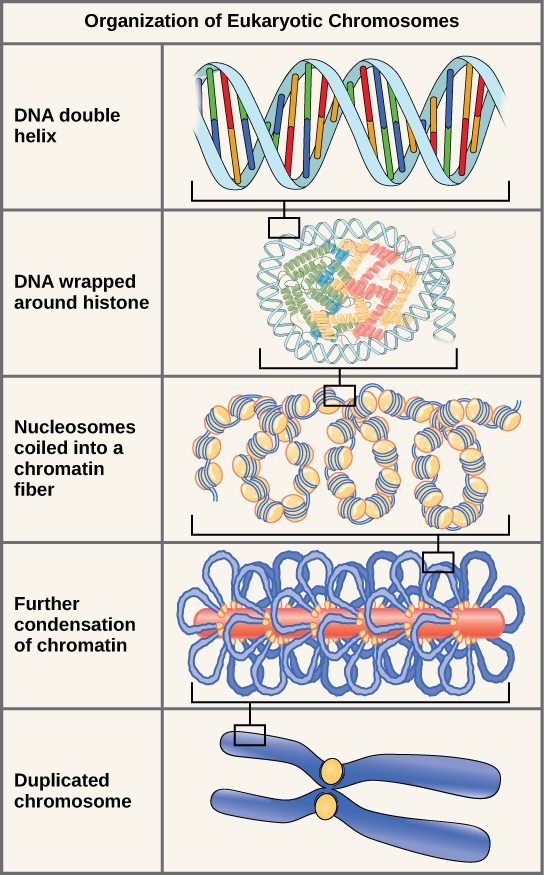

If the DNA from all 46 chromosomes in a human cell nucleus were laid out end-to-end, it would measure approximately two metres; however, its diameter would be only 2 nm! Considering that the size of a typical human cell is about 10 µm (100,000 cells lined up to equal one metre), DNA must be tightly packaged to fit in the cell’s nucleus. At the same time, it must also be readily accessible for the genes to be expressed. For this reason, the long strands of DNA are condensed into compact chromosomes during certain stages of the cell cycle. There are a number of ways that chromosomes are compacted.

Eukaryotes, whose chromosomes each consist of a linear DNA molecule, employ a different type of packing strategy to fit their DNA inside the nucleus (Figure 8.16). At the most basic level, DNA is wrapped around proteins known as histones to form structures called nucleosomes. The histones are evolutionarily conserved proteins that are rich in basic amino acids and form an octamer composed of two molecules of each of four different histones. The DNA (remember, it is negatively charged because of the phosphate groups) is wrapped tightly around the histone core. This nucleosome is linked to the next one with the help of a linker DNA. This is also known as the “beads on a string” structure. With the help of a fifth histone, a string of nucleosomes is further compacted into a 30-nm fibre, which is the diameter of the structure. Metaphase chromosomes are even further condensed by association with scaffolding proteins. At the metaphase stage, the chromosomes are at their most compact, approximately 700 nm in width.

In interphase, eukaryotic chromosomes have two distinct regions that can be distinguished by staining. The tightly packaged region is known as heterochromatin, and the less dense region is known as euchromatin. Heterochromatin usually contains genes that are not expressed, and is found in the regions of the centromere and telomeres. The euchromatin usually contains genes that are transcribed, with DNA packaged around nucleosomes but not further compacted.

A variety of fibrous proteins is used to “pack the chromatin.” These fibrous proteins also ensure that each chromosome in a non-dividing cell occupies a particular area of the nucleus that does not overlap with that of any other chromosome.

This animation illustrates the different levels of chromosome packing.

Section Summary

The currently accepted model of the double-helix structure of DNA was proposed by Watson and Crick. Some of the salient features are that the two strands that make up the double helix have complementary base sequences and anti-parallel orientations. Alternating deoxyribose sugars and phosphates form the backbone of the structure, and the nitrogenous bases are stacked like rungs inside. The diameter of the double helix, 2 nm, is uniform throughout. A purine always pairs with a pyrimidine; A pairs with T, and G pairs with C. One turn of the helix has 10 base pairs. Prokaryotes are much simpler than eukaryotes in many of their features. Most prokaryotes contain a single, circular chromosome. In general, eukaryotic chromosomes contain a linear DNA molecule packaged into nucleosomes, and have two distinct regions that can be distinguished by staining, reflecting different states of packaging and compaction.

Prokaryotes have a single circular chromosome composed of double-stranded DNA, whereas eukaryotes have multiple, linear chromosomes composed of chromatin wrapped around histones, all of which are surrounded by a nuclear membrane. The 46 chromosomes of human somatic cells are composed of 22 pairs of autosomes (matched pairs) and a pair of sex chromosomes, which may or may not be matched. This is the 2n or diploid state. Human gametes have 23 chromosomes, or one complete set of chromosomes; a set of chromosomes is complete with either one of the sex chromosomes, X or Y. This is the n or haploid state. Genes are segments of DNA that code for a specific functional molecule (a protein or RNA). An organism’s traits are determined by the genes inherited from each parent. Duplicated chromosomes are composed of two sister chromatids. Chromosomes are compacted using a variety of mechanisms during certain stages of the cell cycle. Several classes of protein are involved in the organization and packing of the chromosomal DNA into a highly condensed structure.

Exercises

Glossary

electrophoresis: technique used to separate DNA fragments according to size

Media Attribution

- Figure 8.10(a) modification of work by Marjorie McCarty, Public Library of Science

- Figure 8.11 modification of work by Jerome Walker, Dennis Myts

- Figure 8.13 by James Jacob, Tompkins Cortland Community College